Growing up, I’d never been a big fan of geography. It was probably because of how it was taught in school - in silos.

You learn about a river, where it is located and what its dimensions are in the geography class, but you’ll learn about its significance or people who thrived around it in history and maybe about its flora/ fauna in biology.

You are not told a coherent story, instead you are handed off random data points about places you’ve never heard of, that you will need to remember for a test.

So, it’s no surprise that I had no clue about the culinary diversity of the Netherlands until I visited Amsterdam in 2016.

Netherlands

When I landed there, my first stop was Saravana Bhavan. I’d been away from home for 5 months, and I was pregnant. So, I was craving a hearty South Indian meal. More often than not, South Indian meal outside India is equal to Tamil food. May be Telugu too, if you are in the US.

But if you’ve noticed, you don’t find many Kannada restaurants around the world. You might see Udupi restaurants in the Middle East, but Mysore cuisine? Tough luck.

This could just be a function of the extent of Tamilian migration over the last 75 years. The British took a lot of Tamilians both as administration officers and indentured labour to their various colonies, and hence, today’s Tamilian diaspora is diverse.

I wonder if Kannadigas ever had an opportunity and opted out, or never qualified?

Wait, no. That was not the culinary diversity I wanted to talk about.

Second Derivative Migration

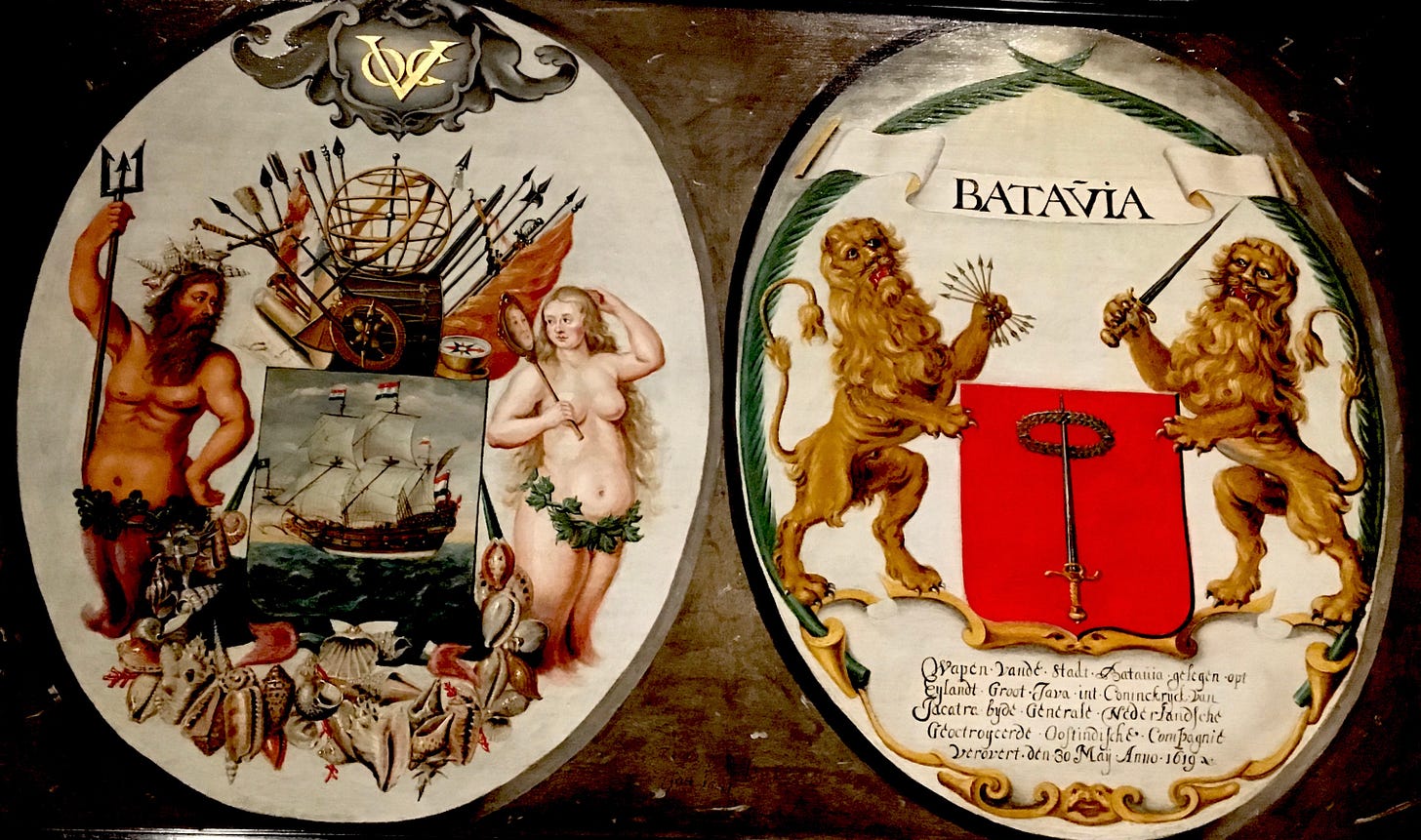

In the 18th century, the Dutch took a lot of indentured labour from their colonies across the world (Indonesia, India, China, etc.) to work in their sugar plantations in Suriname. Over the years, some of these people have moved from Suriname to the Netherlands and have settled there.

To think of it - the Dutch had traded away Manhattan to the Brits, in exchange for what was then the very valuable plantation colony of Suriname! Just based on culinary diversity, I’d say it wasn’t a terrible trade. As for the rest, …

Anyway, there are a lot of “second derivative” migrants in Netherlands, adding to its cultural diversity, and you can see most definitely see that in the food.

The first night that we were there, the husband wanted to take me to Warung Spang Makandra, a Dutch-Surinamese-Indonesian restaurant for dinner. Unfortunately, they were closed for the night. So, we ended up going to Albina, a Dutch-Surinamese-Chinese restaurant.

I’ve never been to mainland China (not the one in India!), so I couldn’t really contrast the taste to authentic Chinese cuisine, but it was definitely nothing like anything I’d had before in any Chinese restaurant across the world. It was a beast of its own. My unborn child truly enjoyed the meal that night, I could tell.

Believe it or not, I learnt about the existence of Suriname only on this trip. Recently, I was in Jordan, and some of my co-travellers were from Suriname. They told me “we are from a place called Suriname, it’s near Brazil”, I was ecstatic to tell them that I already knew where Suriname is and that I love their food.

On our next trip to Amsterdam in 2018, we managed to grab lunch at Warung Spang Makandra. It was rather interesting, different from local Indonesian food. But luckily, by this point, I’d spent enough time in Indonesia to be able to tell the difference.

In fact, this was quite different even from the Dutch-Indonesian cuisine we tried at Sampurna, a fine dining restaurant at the flower market in Amsterdam. We had something called rijjstaffel, or a rice plate which is basically Indonesian food for white (Dutch) people.

The closest local cousin of this foreign variant might be the Padang cuisine (more about this in my Indonesian episode). Indonesian-Dutch food is like the British-Indian curry, a new species, one that you’ll never spot in India.

Anyway the big difference between the different cuisines was the spice level.

Indonesian > Indonesian-Surinamese > Indonesian-Dutch

I don’t think spicy food travels well across different geographies, especially in different weather conditions. It is heavily influenced by availability of local ingredients and the target audience.

Then again, as you’d expect with any migrant food, only a small subset really travels across the world. If you want to experience the full diversity of Indonesian cuisine, beyond the Javanese cuisine that is more widespread, you’ll have to travel extensively across the islands.

*

Next, we went to this spectacular Dutch-Indian-Surinamese restaurant called Roopram Roti. I will take this distortion to Indian food anyday over the British curry. We ate a plate of chicken curry with green beans and potato. Just writing about it now makes me want to apparate to Amsterdam this instance.

Again, it’s nothing like you’ll ever eat in India, it’s a new species, but one that’s worth travelling all the way to Amsterdam for.

My understanding of Suriname is derived from these colonial experiences only. Someday, I’d love to go to Suriname and experience their culture fully, beyond the diversity brought in by the various immigrants (Indian, Chinese, Indo, French, Portuguese, Jewish, African, etc.), assuming they have some native culture left?

As for the local dutch cuisine, we went to a restaurant called Moeders. Super quirky place, great vibe and good food. But I’ll be honest - I was much more excited to discover the migrant food scene in Amsterdam, because it had opened up a whole new world to me (quite literally!).

*

I live in Bangalore, India’s silicon valley, a melting pot of migration from across the country, especially in the last 25 years. During my lifetime, I’ve definitely seen an evolution in our cuisine - influences from various parts of the country and the world.

If there’s something about our culinary culture that I’d call native, it’s probably the concept of darshini, or standing South Indian fast food joints? Although it’s a relatively new concept (from the late 80s), given that’s been a constant through my life time in this city, it feels native enough.

There are variants of darshinis in other countries - Berlin, Tokyo, etc., but I don’t think I’ve seen darshinis anywhere else in India. At least, they aren’t as widespread as they are here in Bangalore.

I don’t know if we have a local Bangalore cuisine, apart from being a variant of the Mysore cuisine, but our association with food is very strong.

The traditional greeting in Kannada, especially in Bangalore, as I’ve seen growing up, is people asking each other “thindi aiyta?” or “oota aiyta?” instead of “what’s up?” or “how are you?”

I mean, is there any other culture that places this much emphasis on food in our lives?

Standard South Indian/Mysore fare is quite common as you say. What I find interesting is the phenomenon of "North Indian meals" in our darshinis. I feel they have their own distinct taste different from what one finds in North India.

Also Kannadigas by the way of not having direct British rule or we were split between different political units or rather we were always self sufficient owing to our geography (sea, mountains, farmland , rivers). Or perhaps a lack of ambition have always stayed put in Karnataka. When communities migrate they attain a sharpness to their own identity which non-immigrant communities dont as they take their identity for granted. Now that Kannadigas are migrating due to IT maybe we see a change in the coming decades.